Hole in your soul

2010/108m

2010/108m

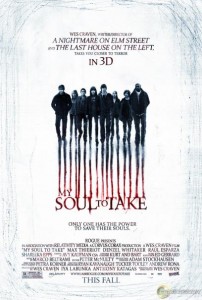

“Only one has the power to save their souls.”

Director/Writer: Wes Craven / Cast: Max Thieriot, Emily Meade, John Magaro, Zena Grey, Nick Lashaway, Paulina Olszynski, Denzel Whitaker, Jeremy Chu, Jessica Hecht, Frank Grillo, Raul Esparza, Danai Gurira, Harris Yulin.

Body Count: 10

Dire-logue: “If things get too hot, turn up the prayer conditioning.”

Unaninmously slated upon its US release in October 2010, Wes Craven’s first written and directed horror flick since New Nightmare holds the rather prickly honor of having the lowest grossing opening weekend for a 3D movie to date.

But then, by that October, there was barely a cinema on the planet that didn’t have at least one 3D feature playing at any given time. Piranha 3D didn’t rake in the wads that they expected and for reasons unknown, My Soul to Take was stuffed into the post-production 3D-ifying machine seemingly to bolster its chances of doing any business.

Time was, Wes Craven’s name attached should get bums on seats but the last Scream flick was a decade earlier (the fourth movie’s imminence notwithstanding) and remember if you will the mess that was Cursed? His last semi-successful output was 2005’s Red Eye, which was a pretty good distraction, if barely a horror film at all. So what went askew with My Soul to Take?

The story goes like a combo of Elm Street and 1989’s clunky Shocker: in the small township of Riverton, a family man has a schzoid-psychotic break and discovers he is the Riverton Ripper, the serial killer who has been terrorising the locale of late. He flips, slays his pregnant wife and is gunned down by the cops but won’t seem to die. In a true Halloween 4-style ambulance crash, his body disappears into the (Riverton?) river and is never seen again. Simultaneously, six women in the town go into labour – hmmm.

The story goes like a combo of Elm Street and 1989’s clunky Shocker: in the small township of Riverton, a family man has a schzoid-psychotic break and discovers he is the Riverton Ripper, the serial killer who has been terrorising the locale of late. He flips, slays his pregnant wife and is gunned down by the cops but won’t seem to die. In a true Halloween 4-style ambulance crash, his body disappears into the (Riverton?) river and is never seen again. Simultaneously, six women in the town go into labour – hmmm.

Sixteen years later, a group of kids known as The Riverton Seven who were all born that night gather for Ripper Day, an annual sorta rite-of-passage event. One of the kids was predictably born to the Ripper’s dead wife and seems to have inherited dad’s schizophrenia and so could just be the one who starts knocking off the others throughout the course of the day.

In the first instance, My Soul to Take plays out like any other slasher flick: we meet the meat: five boys and two girls who all turn sixteen together. Bug is instantly singled out as the lead, a quirky brooding sort who has a history of mental unbalance but is strangely the object of lust for several girls at school, including his two female birth-mates, devout Christian Penelope (who can sense something bad coming) and valley girl-lite Brittany, who bows to every command of the school Queen Bee, Fang. There’s also jock bully Brandon, token Asian Jay, blind black guy Jerome and Bug’s bestie Alex.

The high school melodrama is entertainingly surreal: Fang dictates almost everything, from who gets hit and how hard to who her following of airhead girls can and can’t have the hots for. And Bug is off the list.

The high school melodrama is entertainingly surreal: Fang dictates almost everything, from who gets hit and how hard to who her following of airhead girls can and can’t have the hots for. And Bug is off the list.

There’s an amusing show-and-tell scene where Bug and Alex present a piece on the Great American Condor and get some semblance of revenge on Brandon and then things shift into horror gear proper as the teens start piling up dead, stalked and offed by a loon dressed as the Riverton Ripper (mangy coat, plastic mask and dread-like hair) who eventually decides to pay a visit to Bug’s place.

Considering the film nearly reaches two hours, it’s amazing how few scenes there are: after it gets going, we jump from murder to murder for a time and then everything else occurs at Bug’s house, where a midriff revelation about his and Fang’s relationship opens up some questions about the past before we find out just who is possessed by the Ripper’s vengeful spirit.

Up until this point, I was wondering why everyone viewed My Soul to Take so harshly. Then came the ending. I’m not sure I’ve ever experienced such a flaccid, rookie climax as this – it just…happens. Craven didn’t put the strongest finale on Elm Street and I’ve never minded that but it’s as if he got to the last page of the script and thought “bollocks! I’ve completely forgotten to think up an ending for this!” and just grabbed the nearest feasible character to make the possessee.

The gravity of how flat the ending is easily robs a star from the rating but even so, Craven’s direction feels restrained and almost pedestrian when we’re all too aware of what he’s capable of achieving on a tight budget. The film looks better than most but there’s nothing – visually or scripted – that has his stamp on it and some of the characterisations leave a lot to be desired.

The gravity of how flat the ending is easily robs a star from the rating but even so, Craven’s direction feels restrained and almost pedestrian when we’re all too aware of what he’s capable of achieving on a tight budget. The film looks better than most but there’s nothing – visually or scripted – that has his stamp on it and some of the characterisations leave a lot to be desired.

Curiously, the most intriguing character is Penelope, who speaks to God as if he’s beside her and has some idea of the storm that’s coming and yet she’s rather heartlessly killed off early on. It would’ve been easy to turn her into a parody of the middle-American religious zealot but Craven succeeds in drawing out her personality, which is probably the most appealing on show, but then elects bitchy Fang as a sort of secondary hero? What gives, Wes?

Elementally, a frustrating film that seems to have arrived about fifteen years too late and a bit of a bum note for Craven, although not as dire as many have cited.

Blurbs-of-interest: Frank Grillo was in iMurders; Harris Yulin was in the Elm Street cash-in Bad Dreams; Music was by Marco Beltrami, who worked on all three Scream movies. Craven’s other slasher flicks include The Hills Have Eyes Part II and Deadly Blessing.

I was really excited to go see this one, I mean, a new Wes Craven movie about a slasher? done and done! So I went to go see this at the drive in opening night and boy during the first 10 minutes I knew something was dangerously wrong. I was lost the entire time, granted i was stoned out my gourd but still, i even got the munchies during the middle of the movie and I actually got out of the car and walked to the snack bar, something i NEVER do during a movie,ESPECIALLY horror, I held my pee for the entire running time of Piranha and it was worth it, but this movie was just..a disaster..thank god the tickets were only $3

The fact you got to see it at a drive-in is amazing!! It was a shame it didn’t pan out for ol’ Wes… Fingers crossed for Scream 4.

Hud

hud,

i know, the drive in down here is great, it’s a 14 screen drive in so they always got all the new releases,what sucks is that they never play any old movies 🙁

Trade-a-Life III: Penelope~Fang?

When I read the original script–which was much less of a slasher film–I actually thought Penelope was going to be one of the survivors. She wasn’t, but her death was different than in the final film.

Yes!

I really liked what they did with Penelope, whereas they tried to play it cool with Fang and screwed it up completely.

– Hud

In 2015, I wrote a review of MY SOUL TO TAKE and posted it at Dooovall dot blogspot dot com, which is now an archive of assorted horror film reviews that I cranked out over a few autumns.

Here’s my review of Craven’s 2010 film – a counterpoint to the points made above.

Written and directed by Wes Craven, My Soul to Take met with harsh reviews upon its theatrical release in October of 2010. In Variety, Dennis Harvey called the film a “dumb, derivative teen slasher movie” and “a pretty soporific affair bogged down by awkward expository dialogue, one-dimensional characters (or ones whose suggested hidden sides turn out to be mere tease), bland atmospherics and unmemorable action.” Gary Goldstein (in the L.A. Times) opined that the project is “a thrill-free snooze” with an “overly complex story.” Marc Savlov wrote in The Austin Chronicle that “this utterly mediocre forget-me-now could’ve been crafted by any faceless serial director.” I beg to differ with these three critics and all the others who dismissed My Soul to Take, which I perceive as a flawed but thought-provoking singular horror tale with ample scares and a core concept that demands repeat viewings to fully appreciate.

The movie opens with a gripping nine-minute prologue set sixteen years before the main story. In the opening sequence, a family man named Abel (who suffers from multiple personality disorder) finds a distinctive knife in his workshop and recognizes the weapon from TV news reports as the blade of choice used by a local serial killer (the Riverton Ripper). Fearing that one of his heretofore unknown personalities might be responsible for a string of murders, Abel phones his psychiatrist but then notices that his pregnant wife has already been knifed. Authorities arrive and shoot Abel as he’s about to kill Leah (his three-year-old daughter). Abel snatches a gun from one officer, shoots him, and then offs his doctor before another cop takes him down. Wounded but alive, Abel revives in an ambulance en route to the hospital (where mysteriously seven premature births are happening) and causes a nasty crash (the vehicle flips, rolls, and ultimately explodes alongside a river). When help arrives, Abel’s body is nowhere to be found.

Sixteen years later, the seven kids born the night of the prologue ring in their sixteenth birthday with a tradition known as “Ripper Night” alongside the river (by the remains of the ambulance, now rusted out and covered in candle stubs) during which one of the “Riverton Seven” must fend off a massive puppet designed to look as Abel might appear had he survived and lived in the wilderness all this time (ragged clothing, long hair, and a scraggly beard). Protagonist Adam “Bug” Hellerman (a sensitive fellow prone to migraines) is this year’s “volunteer,” and he’s spooked by the sight of the puppet. Before the ritual goes far, police arrive and order the teens to disperse. On his way home, Jay (one of the Riverton Seven) notices someone following him as he crosses an isolated bridge. Chased down by a long-haired bearded fellow in ragged clothes, Jay dies around seventeen minutes into the tale when his assailant slams his head against a metal post, knifes him, and tosses him into the river.

The next forty minutes of the film happen during daylight as the teens (unaware that one of their peers has been murdered) go about a typical day before, during, and after school. A female student nicknamed Fang holds sway over many friends and followers; she makes life hell for Bug and his best friend Alex, ordering a bully (Brandon) to rough them up. Thirty-three minutes into the film, Bug has a vision and sees (in a restroom mirror) Jay, bloody, swimming underwater. Six minutes later, Craven begs the viewer to wonder just what the hell is going on when Bug and Alex (alone in a corridor) begin speaking in unison and moving as if they are mirror images of one another for a minute or so. Just under ten minutes later, the present-day Ripper claims another victim and slits the throat of Penelope (a religious gal and one of the Riverton Seven) alongside the school’s pool. Within eleven minutes, two more victims fall to the mysterious killer (who may or may not be Abel): Brandon and the young woman he lusted after (Brittany).

Night falls again one hour into the film, and the rest of the action plays out in and around Bug’s home that evening. Craven reveals that “Fang” is Bug’s sister and is in fact Leah (Abel’s daughter), and the woman Bug thought was his mother turns out to be his aunt (paramedics cut Bug out of his dead mom’s womb the night of the prologue). Eighty-one minutes into the story, the protagonist finds himself confronted by a cop who thinks that Bug’s responsible for the four teens killed that day, and Bug finds that his aunt has also been killed. The Ripper shows up, kills the officer, and attacks Bug. I won’t spoil the beat-by-beat moments of the denouement, but I will reveal the twist that confused many critics and may not be apparent until a second viewing: the night Abel died in the prologue, his seven personalities (each a unique soul) dispersed and reincarnated as the Riverton Seven, and one of them is the present-day killer. I won’t tell you which one, though there are only three suspects left as the finale gets well and truly underway.

My only quibble with this film is that Alex (ninety-one minutes into the story) tells Bug that Abel developed “schizophrenia” at the age of sixteen. Schizophrenia has nothing to do with multiple personalities (contrary to popular opinion) and is a wholly different sort of mental illness.

“This was a script that got rewritten while we were shooting,” Wes Craven notes on the Blu-ray’s audio commentary track. “It’s a very complex story, and we kept figuring out how to make it better.” While some critics see the plot’s complexity as a negative, I enjoyed watching a horror yarn in which not everything’s spelled out even by the time one reaches the very end. My Soul to Take is a wrongly-maligned entry in Wes Craven’s oeuvre, and I predict that it shall be rediscovered and reevaluated in due time. Thought-provoking, sometimes puzzling, but always entertaining, My Soul to Take is a unique spin on the “teens in jeopardy as a knife-wielding killer stalks them” sub-genre.